Flies like yellow, bees like blue: How flower colors cater to the taste of pollinating insects

We all know the birds and the bees are important for pollination, and we often notice them in gardens and parks. But what about flies?

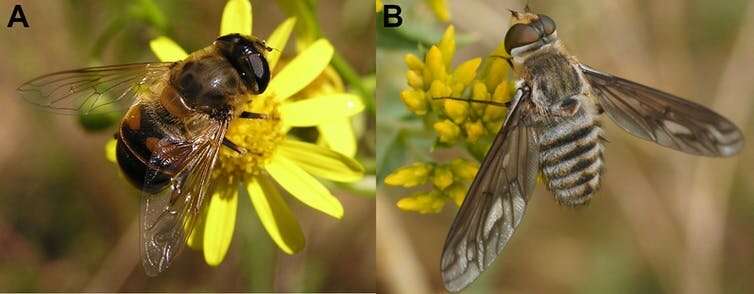

Flies are the second most common type of pollinator, so perhaps we should all be taught about the bees, the flies and then the birds. While we know animals may see color differently, little was known about how fly pollination shapes the types of flowers we can find in nature.

In our new we address this gap in our knowledge by evaluating how important fly pollinators sense and use color, and how fly pollinated flowers have evolved color signals.

The way we see influences what we choose

We know that different humans often have preferences for certain colors, and in a similar way bees prefer .

Our colleague Lea Hannah has observed that hoverflies (Eristalis tenax) are much better at than between different blues. Other research has also reported hoverflies have .

Many flowering plants depend on attracting pollinators to reproduce, so the appearance of their flowers has evolved to cater to the preferences of the pollinators. We wanted to find out what this might mean for how different insects like bees or flies shape flower colors in a complex natural environment where both types of insect are present.

The Australian case study

Australia is a natural laboratory for understanding flower evolution due to its . On the mainland , flowers have predominately .

Around Australia there are plant communities with different pollinators. For example, has no bees, and flies are the only animal pollinator.

We assembled data from different , including a native habitat in mainland Australia where both bees and flies forage, to model how different insects influence flower color signal evolution.

Measuring flower colors

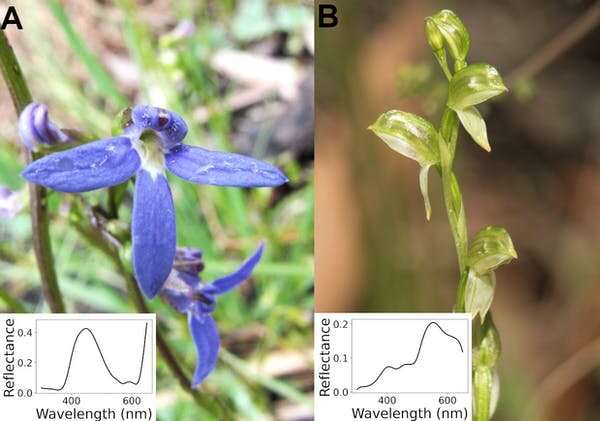

Since we know different animals sense color in different ways, we recorded the spectrum of different wavelengths of light reflected from the flowers with a spectrometer. We subsequently modeled these spectral signatures of plant flowers considering animal perception, allowing us to objectively quantify how signals have evolved. These analyses included mapping the of the plants.

Generalization or specialization?

According to one school of thought, flower evolution is driven by competition between flowering plants. In this scenario, different species might have very different colors from one another, to increase their chances of being reliably identified and pollinated. This is a bit like how exclusive brands seek customers by having readily identifiable branding.

An alternative hypothesis to competition is facilitation. Plants may share preferred color signals to attract a higher number of specific insects. This explanation is like how some competing businesses can do better by being physically close together to attract many customers.

Our results demonstrate how flower color signaling has dynamically evolved depending on the availability of insect pollinators, as happens in marketplaces.

In Victoria, flowers have converged to evolve color signals preferred by their pollinators. The flowers of fly-pollinated orchids are typically yellowish-green, while closely related orchids pollinated by bees have more bluish and purple colors. The flowers appeared to share the preferred colors of their main pollinator, consistent with a facilitation hypothesis.

Our research showed flies can see differences between flowers of different species in response to the pollinator local "market."

On Macquarie Island, where flies are the only pollinators, flower colors diverge from each other—but still stay within the range of the flies' preferred colors. This is consistent with a competition strategy, where differences between plant species allow flies to more easily identify the color of recently visited flowers.

When both fly and bee pollinators are present, flowers pollinated by flies appear to "filter out" bees to reduce the number of ineffective and opportunistic visitors. For example, in the Himalayas specialized plants require . This is similar to when a store wants to exclusively attract customers specifically interested in their product range.

Our findings on fly color vision, along with novel precision , can help using flies as alternative pollinators of crops. It also allows us to understand that if we want to see a full range of pollinating insects including beautiful hoverflies in our parks and gardens, we need to plant a range of flower types and colors.

More information: Jair E. Garcia et al, Fly pollination drives convergence of flower coloration, New Phytologist (2021).

Journal information: New Phytologist

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from under a Creative Commons license. Read the .![]()