November 15, 2012 report

Astrophysicist suggests planetary misalignment due to multiple star impact

(Â鶹ÒùÔº)—Astrophysicist Konstantin Batygin has published a paper in the journal Nature arguing that the reason some planets lie in a tilt off the equatorial plane of their sun is because of the prior existence of another star that impacted their orbit. He suggests that systems that once hosted more than one star, but now do not, could also explain the existence of "Hot Jupiters" that have an orbit opposite of their host star.

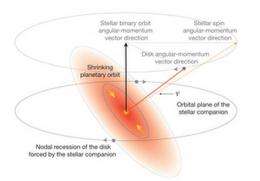

"Hot Jupiters" are large, Jupiter-like planets that orbit very closely to their star. First discovered in 1995, it was assumed they formed at some distance from their host star and then migrated closer over time due to gravitational pull from gasses and dust around the star. Such a theory would suggest that the planet would naturally orbit in alignment with the star's equator. That theory was dashed however, when in 2008, researchers discovered that some Hot Jupiters did not have aligned orbits and that some in fact actually orbited in reverse of their sun. New theories have suggested this was due to the pull of other planets as the Hot Jupiter made its way closer to the star. Now, Batygin proposes another possibility – that the misalignment is due to the gravitational effects of another star that used to be part of the system, but has since departed.

Batygin notes that most solar systems today are binaries, and that some systems have more than two stars. To try to understand what sort of impact multiple stars might have on planets in those systems, he built and ran computer models. His simulations showed that disruptions to a planet's orbital path could very easily explain why some systems show a total misalignment of all its planets and that given the right circumstances, a complete flip-flop could occur, resulting in a planet orbiting in an opposite direction to their stars' spin. He adds that because the solar system in which Earth resides has a 7 degree tilt, it's very likely that one of the stars out there in the Milky Way today, once was part of our own solar system. He also suggests that it might be possible to strengthen his theory by comparing all of the known binary star formations with all known misaligned exoplanet systems.

More information: A primordial origin for misalignments between stellar spin axes and planetary orbits, Nature, 491, 418–420 (15 November 2012)

Abstract

The existence of gaseous giant planets whose orbits lie close to their host stars ('hot Jupiters') can largely be accounted for by planetary migration associated with viscous evolution of proto-planetary nebulae. Recently, observations of the Rossiter–McLaughlin effect during planetary transits have revealed that a considerable fraction of hot Jupiters are on orbits that are misaligned with respect to the spin axes of their host stars3. This observation has cast doubt on the importance of disk-driven migration as a mechanism for producing hot Jupiters. Here I show that misaligned orbits can be a natural consequence of disk migration in binary systems whose orbital plane is uncorrelated with the spin axes of the individual stars. The gravitational torques arising from the dynamical evolution of idealized proto-planetary disks under perturbations from massive distant bodies act to misalign the orbital planes of the disks relative to the spin poles of their host stars. As a result, I suggest that in the absence of strong coupling between the angular momentum of the disk and that of the host star, or of sufficient dissipation that acts to realign the stellar spin axis and the planetary orbits, the fraction of planetary systems (including systems of 'hot Neptunes' and 'super-Earths') whose angular momentum vectors are misaligned with respect to their host stars will be commensurate with the rate of primordial stellar multiplicity.

Journal information: Nature

© 2012 Â鶹ÒùÔº