Searching for heavy new particles with the ATLAS Experiment

Since discovering the Higgs boson in 2012, the ATLAS Collaboration at CERN has been working to understand its properties. One question in particular stands out: why does the Higgs boson have the mass that it does? Experiments have measured its mass to be around 125 GeV—yet the Standard Model and requires a very large correction to the mathematics in order to align theory with observation, leading to the "naturalness problem."

This discrepancy could be resolved if a new type of interaction existed, in addition to the four known fundamental forces (gravity, electromagnetism, strong and weak). This interaction would result in new force-carrying particles (bosons) with masses much larger than anything currently in the Standard Model. Among several theories describing this interaction are the "heavy vector triplet" (HVT) models, which suggest that a new particle—the "W prime" (W') boson—could be produced with the collision energies accessible at the LHC. As the name implies, these new heavy particles would interact with the electroweak force and, after being produced in a collision, would very quickly decay into a W boson and Higgs boson.

A from the ATLAS Collaboration, released this week at the Large Hadron Collider Â鶹ÒùÔºics conference (LHCP 2021), sets limits on the mass of the W' boson, using the full LHC Run 2 dataset collected between 2015 and 2018. The search targets the "semileptonic" final state, where the Higgs boson decays into a pair of b-quarks, and the W boson decays into both a neutrino and one electron, muon or tau lepton.

The wide range of possible masses for the W' boson—from 400 GeV to 5 TeV—presented ATLAS physicists with some unique challenges. If the W' mass is on the heavier end of the predictions, it would produce Higgs bosons with higher energies and the resulting b-quarks would emit two "jets" (collimated sprays of particles) that are so close together as to appear as a single jet with a large radius in the ATLAS detector. Smaller W' masses, on the other hand, would appear as two distinct jets. To account for this great variation of features, the new ATLAS analysis studied multiple distinct channels, each specifically optimized to provide the best sensitivity to the new particle.

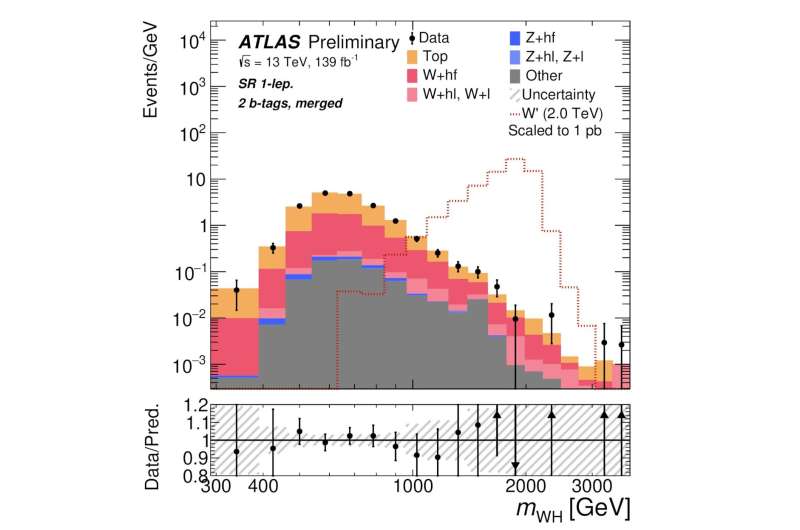

As seen in Figure 2, many far more common Standard Model processes may result in the same signature as the W' decay, so it's crucially important to eliminate as much of this Standard Model background as possible. ATLAS physicists employed a multi-variate algorithm that used certain kinematic features of b-quark decays to try to distinguish their decay jets from other, lighter flavors of hadrons, creating "one b-tag" and "two b-tag" regions. Additionally, improving on the previous search for W' bosons with a partial Run 2 dataset, researchers utilized novel techniques to identify and measure jets in the detector. "TrackCaloCluster" jets combined information from ATLAS' inner tracking system and electromagnetic calorimeter, while "Variable Radius" jets could more efficiently identify Higgs bosons by allowing the radius of its decay jets to change with different amounts of momentum.

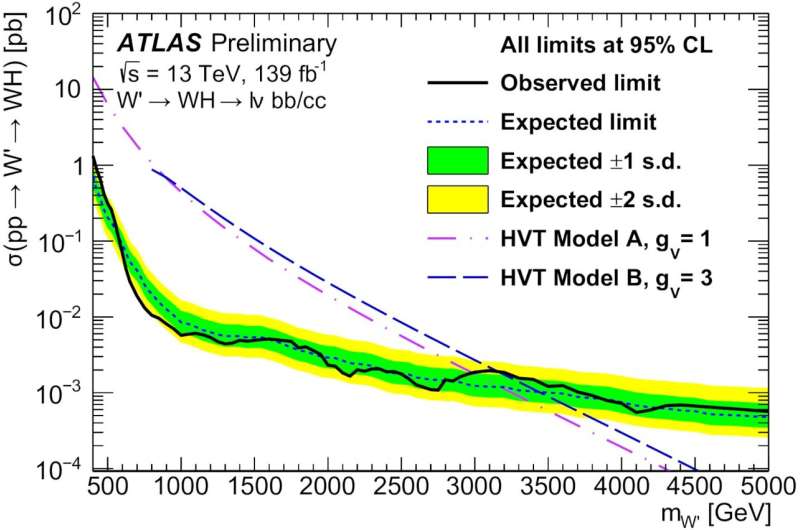

Â鶹ÒùÔºicists found no statistically significant evidence of a deviation from the Standard Model in their search. The results were used to set new limits, shown , on the mass of a hypothetical W' boson, excluding masses up to 3.15 TeV, which is a nearly 12% increase from the previous ATLAS search for a HVT W' boson with a partial Run 2 dataset. The hunt for new physics continues!

More information: Search for heavy resonances decaying into a W boson and a Higgs boson in final states with leptons and b-jets in 139 fb−1 of proton–proton collisions at 13 TeV with the ATLAS detector (ATLAS-CONF-2021-026):

Provided by ATLAS Experiment