The debut of the antihydrogen beam

The standard model of particle physics suggests that matter and antimatter are equal and opposite in every way. Yet the observable Universe is made almost entirely of matter—an asymmetry that remains one of the greatest unsolved mysteries in physics.

In an advance that could make it possible to search for tiny differences between matter and antimatter and help to explain their imbalance in the cosmos, Yasunori Yamazaki and colleagues from the RIKEN Atomic Â鶹ÒùÔºics Laboratory, in collaboration with researchers from around the world, .

Hydrogen contains a positively charged proton and a negatively charged electron. The electron can occupy two slightly different ground states depending on how its spin aligns with the proton's spin—a distinction known as hyperfine splitting.

Antihydrogen, on the other hand, consists of a negatively charged antiproton and a positively charged antielectron—or positron. One of the core tenets of the standard model—charge–parity–time (CPT) symmetry—dictates that antihydrogen should exhibit exactly the same hyperfine splitting as hydrogen. "If it is different," says Yamazaki, "we can immediately conclude that CPT symmetry is violated, and the standard model should be replaced by some other theory."

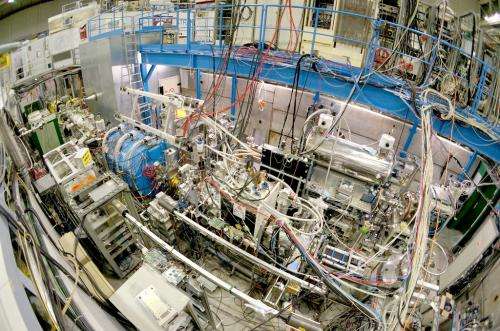

Measuring the hyperfine splitting of antihydrogen is extremely difficult. Since antimatter is instantly annihilated when it comes into contact with ordinary matter, researchers trap it using magnetic fields. However, magnetic fields can alter the energy of the hyperfine transition, making the measurement less precise. To avoid this, Yamazaki and his co-workers involved in the ASACUSA (Atomic Spectroscopy and Collisions Using Slow Antiprotons) experiment at the CERN (European Organization for Nuclear Research) particle physics facility instead produced a beam of antihydrogen atoms that can be detected at a distance, away from any interfering magnetic fields.

The antihydrogen beam is produced by mixing antiprotons and positrons in a special alignment of magnetic and electric fields known as a cusp trap. The antihydrogen atoms escape the trap as a beam and can be detected 2.7 meters away. Lower-energy antihydrogen atoms will be needed, however, to measure hyperfine splitting. "Our next goal is to produce a 'cold' beam of antihydrogen atoms in the ground state," says Yamazaki.

The test for hyperfine splitting will involve exciting the antihydrogen atoms using 1.4 gigahertz radiowaves, which can cause the spontaneous change from one spin alignment to the other. The research team is hopeful that these groundbreaking tests could be run by the end of 2014.

More information: Kuroda, N., Ulmer, S., Murtagh, D. J., Van Gorp, S., Nagata, Y., Diermaier, M., Federmann, S., Leali, M., Malbrunot, C., Mascagna, V. et al. "A source of antihydrogen for in-flight hyperfine spectroscopy." Nature Communications 5, 3089 (2014).

Journal information: Nature Communications

Provided by RIKEN